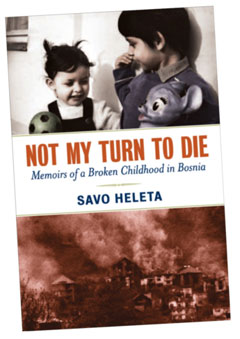

Growing up in Goražde, Bosnia, Savo Heleta did not think about ethnicity, race or religion. Everyone knew one another in the small peaceful city, his best friend was Muslim, and most considered themselves “Yugoslav.” In Not My Turn to Die (March 2008, AMACOM Books, New York), Heleta describes (perhaps a bit too simply) how nationalist politicians led the country into war, but this is certainly not a story about politics. He provides a gripping account of his family’s struggle for survival during the first two years of the war, through constant shelling, murder attempts, degradation and forced starvation. His family was among the few Serbian civilians that stayed in Goražde, a Muslim dominated city, and ironically, they suffered through shelling and sniper attacks from their own ethnicity. The city was crowded with Bosniak refugees from neighboring towns, and Heleta’s family became isolated in their own home among their neighbors with no connection to the outside world. Simple actions such as retrieving water became a matter of life and death. Eventually his family escaped by swimming in the Drina River to safety, but not until after they lived in complete terror for two years.

Growing up in Goražde, Bosnia, Savo Heleta did not think about ethnicity, race or religion. Everyone knew one another in the small peaceful city, his best friend was Muslim, and most considered themselves “Yugoslav.” In Not My Turn to Die (March 2008, AMACOM Books, New York), Heleta describes (perhaps a bit too simply) how nationalist politicians led the country into war, but this is certainly not a story about politics. He provides a gripping account of his family’s struggle for survival during the first two years of the war, through constant shelling, murder attempts, degradation and forced starvation. His family was among the few Serbian civilians that stayed in Goražde, a Muslim dominated city, and ironically, they suffered through shelling and sniper attacks from their own ethnicity. The city was crowded with Bosniak refugees from neighboring towns, and Heleta’s family became isolated in their own home among their neighbors with no connection to the outside world. Simple actions such as retrieving water became a matter of life and death. Eventually his family escaped by swimming in the Drina River to safety, but not until after they lived in complete terror for two years.

We often read personal accounts of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina from a Muslim perspective and statistically, Serbs were guilty of most of the killing. However, Serbs also were persecuted during the war and suffered extreme losses. Heleta’s memoir describes such experiences. He reminds us that this is only his story, and that he cannot speak for the country as a whole. Often Heleta describes acts of kindness from Muslim neighbors and his detailed, journalistic style is engrossing and sincere. The book is as much about peace as it is about war, and readers witness the transformation of an angry adolescent to a forgiving adult, who studies and works on post-conflict issues in Africa today. I felt privileged to speak with him, and to hear his opinions on the war, life in Bosnia today, and the future of the ethnically partitioned state.

Author Savo Heleta

Christine Bednarz: I’ve really been looking forward to this… I have a lot of questions for you. I enjoyed the book immensely. I found it to be honest, sincere, and as objective as one can be when talking about the former-Yugoslavia.

Savo Heleta: Thanks…and one always has to remember that is a personal story and there are many stories out there. This is only one.

CB: Of course.

SH: People sometimes say to me… “You don’t write about other parts of Bosnia”… well, I was not there.

CB: How do people in Bosnia and the former-Yugoslavia respond to the book in general?

SH: This is quite interesting. People from different sides who read the book say it is a good, very objective book and people who never read the book are critical of it.

CB: That is very interesting. I wonder if some people are afraid of the truth about the wars coming out?

SH: Perhaps…. I always say that there is no one story, one history. We all have our experiences. And sometimes our experiences are quite different from what is presented on CNN for example. In 2008, an online magazine in Bosnia published an interview with me about the book… after that I received death threats from people who never read the book.

CB: Was this your interview with Sarajevo-x.com?

SH: Yes, with Sarajevo-x. Even they at Sarajevo-x were surprised after so much hate mail and comments came after the interview.

CB: I read that interview…

SH: Can you read Serbian/Bosnian/Croatian? Interesting.

CB: Not really… I spent 5 months living Novi Sad studying the language at their university… but I needed a lot of help translating that interview. Look at you- very politically correct by naming all three languages. Any plans to translate your book for the people of the former-Yugoslavia?

SH: Yes, you always have to be PC! I hope to get the book translated soon… at least so my parents and family can read it. They have a copy in English but they can’t read it.

CB: Wow, they haven’t read it yet?

SH: No. My sister did, she could understand it. My cousin tried to translate some of it for my parents and family.

Me: That’s really interesting to me, because the book was as much about your family as it was about you.

SH: Exactly.

CB: They must be very proud of you. What are they doing now?

SH: My dad is a journalist. My mom has her own little business, she makes stuff, like scarves, etc. And my sister lives in Belgrade and works as a graphic designer- a very good one.

CB: Your parents still live in Bosnia?

SH: Yes, they live in Bosnia, in Višegrad… some 30 km from Goražde,, where we used to live.

CB: The Bridge on the Drina. I drove through Višegrad last summer.

SH: Yes, they live very close to the bridge.

CB: The interview with Sarajevo-x mentions your father’s work as a journalist and his part in the documentary Na Drini grobnica…which described Serbian suffering during the war and received quite a bit of criticism for its lack of objectivity. How were your healing processes different?

SH: Actually, my dad was never involved with that documentary… I didn’t know about that documentary and whether he was involved or not at the time I was interviewed… the only involvement he had was to write about it as a journalist after attending a press conference when the film was released. And even if he was involved, why is it a crime to talk about Serbs who were tortured and killed in Goražde,? As I said before, there is always more than one side of every story… nothing is simple, black and white.

CB: Especially when it comes to the former-Yugoslavia. There are many sides, and objectivity must be impossible…although I appreciated your book, especially when you pointed out the help you received from Muslim neighbors, etc.

SH: I had a lot of Serbs telling me that I shouldn’t have written about help we received from our Muslim neighbors and friends…and I dismissed them as I dismissed others. I will say what happened despite the fact that some may not like what I have to say…One of my favorite books is “I Write What I Like” by Steve Biko… he was a South African activist against apartheid who was killed mainly because he wrote against the then racist regime…I hope I don’t get killed though…

CB: I’m not familiar with him… I hope so as well! But of course there are many sides of the story… and of course during a war, all sides suffer extreme losses. This is unavoidable… but in your opinion, who were the real victims of the wars following the breakup of Yugoslavia?

SH: The real victims were civilians, ordinary people, who did not want the war and they are on all sides. Many were killed, many lost family members, homes, property, future. I see all of them as main victims

CB: Many seem quick to place blame or take sides.

SH: That’s the easiest.

CB: Earlier you mentioned CNN and its portrayal of the war. The UN and Red Cross involvement are an interesting part of this book. One month before the fighting broke out in Goražde, the Red Cross staged a fight for bread with 30 refugees and you write, “The scene looked like someone was in the process of making a movie.” Did this sort of thing happen often?

SH: I saw it only once. I’m not sure what happened elsewhere but then there are similar stories from other parts of the world.

CB: And NATO…NATO dropped food for the city and people had to risk their lives looking for it. Your father came home one day after seeing something horrible- a family was waiting for a food drop and it landed right on them, killing them instantly. What could have been different?

SH: Yes, I actually read somewhere else about that same incident when that family was killed by the food drops. I’m not sure what could have been different… the UN forces could have tried to help civilians on all sides…but these things happen… there are over 10,000 UN troops in South Sudan right now and their mission is everything but protection of civilians who are dying in clashes by hundreds every month. So what’s the point in having peacekeepers if they are not there to protect civilians? Does the UN just want to be politically correct and send troops who then do nothing? I keep looking for answers in my research on Sudan and Africa.

CB: That’s a good question. The UN work in Goražde was certainly…inadequate.

SH: And it seems that hardly anyone cares for helping ordinary people. When we saw the first UN convoy entering the city in 1992, we thought that’s it, we are safe from now [on]. They delivered food and left… then the bombs came down on us… This was the first realization that the help we expected from them was not going to be…And the help never came from them… it came from ordinary people who often saved our lives. And there was one UN official who said to us that he was risking his job to take a letter from us and deliver it to the other side so our family can know that we are alive. He did it in his personal capacity.

CB: And it seemed like the food did not always reach the people.

SH: That’s understandable, there was a huge shortage, so much money to be made, those with guns had power over the people without guns so they took advantage.

CB: Yes, your book certainly showed the overall failure of large organizations and highlighted the random acts of kindness of individuals. Luckily your family finally escaped to Višegrad, Serb occupied territory- where your parents live now, by swimming in the Drina River. You felt free again and were even able to return to school. I’m thinking about writing my master’s thesis on education in Bosnia… and your book very briefly mentions the schools in Višegrad. Could you elaborate further? I guess this was at the point when you were finishing primary school and starting high school… is that right?

SH: Yes. At that time I didn’t care about education, which was in a bad state. I hardly went to high school. Our teachers didn’t care, they weren’t getting paid… Many of us students didn’t care about education either. I’m not sure if I’m a good person to talk about education in Bosnia, I may be too critical… I also don’t know how things are since 2002… but during and right after the war the situation with education was bad.

CB: Yes, it seems to me that the partitioned state as a result of the Dayton Peace Agreements created ethnically homogeneous schools that teach their own nationalist position to kids. Which means that unlike in your childhood, the children of Bosnia today are growing up more isolated than ever before…But I realize that education is not your area, and hopefully the situation has improved somewhat since you finished high school.

SH: Yes, I agree with you. And they are getting that divided mentality from primary school… I’m afraid to think how they are going to turn out.

CB: Me too. What’s it like to go back to Bosnia and the region? How do people live? How do they get along today?

SH: I go to visit as much as I can – once a year…. I don’t think there will be any more fighting there, I can’t think of anyone stupid enough to go back to war. I’m afraid that there will be social unrests as the economy is on its knees, there are so many unemployed people… I sometimes don’t understand how people make it. For me personally it is very strange when I go back… living in the US for four years and then moving to South Africa, I have changed completely in every sense… my views, perspectives, interests – I’m perhaps the only Bosnian who is crazy about cricket! And people there seem to be still living in the war-post war state of mind.

CB: You certainly have lived in three very different places: Bosnia, Minnesota and South Africa. Because I’m a American who loves living in Europe… I have to ask- what was it like to leave Bosnia after living through war and go to a place so… materialistic?

SH: It was different… but then I went there to study. I had a different experience than those who go to the US to live and work.

CB: And now you are in South Africa? What are you doing there?

SH: I spent one semester in South Africa in 2005, met a girl – it’s always like that…and then came back in 2007. Finished [my] masters in Conflict Transformation and Management at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in 2009. Now [I’m] doing a PhD in Development Studies, focusing on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development and also working on South Sudan Executive Leadership Program. By the way, the New York Times, Washington Post, etc. published a story about us today. We are quite proud today.

CB: Congratulations…that’s quite the recognition. I’m sure your life experiences really prepared you for your work today. But is your work in Bosnia done? Aside from your book promotion and interviews, of course.

SH: People always ask me that…

CB: Sorry to be redundant…but after your work with Peacetrails while many of your friends went a more destructive route… I have to ask.

SH: In terms of my interest, I think I will remain in Africa and work on African conflict and post-conflict issues. I can’t really explain it. This often happens to people who come to Africa… Nothing really matters after that, you just can’t leave.

CB: Well you seem like the type of person who follows his heart. That’s a good thing. In all of your travels and work on three different continents, what do you think is the worldview of the former Yugoslavia?

SH: It’s a bad one of a place where people know nothing but to kill each other… Almost the same as the view of Africa, but when my American friends visit Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia, they enjoy it so much and write to their parents that these places are great, safe, beautiful, etc.

CB: I can relate to that- I think Bosnia is one of the most beautiful countries in Europe. The people in that whole region are some of the nicest, most hospitable people I have ever met anywhere. I hope to move to Bosnia after I finish studying in Poland. Okay, I know you are busy and I’ve taken up enough of your time already. One last question: What are your hopes and predictions for the future of Bosnia?

SH: I really hope people in Bosnia can move on and start thinking about future… the past is there but we don’t have to live by it. I hope there can be some form of reconciliation as nothing really happened so far and all those who committed crimes should be brought to justice, from all sides.

CB: I hope that Bosnia can find reconciliation as well.

I highly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in the former-Yugoslavia. Please visit Savo Heleta’s website for more information and the book is available for purchase here.